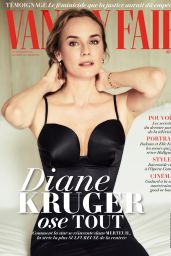

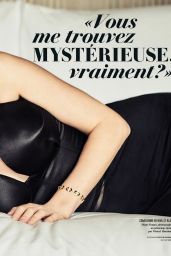

There’s a quiet electricity in these pages—Diane Kruger doesn’t just pose, she inhabits a narrative. Draped in black, whether strapless or cut with a plunging neckline, she becomes both subject and storyteller. The fabrics are matte, the cuts architectural, the atmosphere stripped of distraction. Every frame feels like a still from a film that hasn’t yet been made.

The embedded text sharpens the mood: “Diane Kruger ose TOUT” — she dares everything. It’s not a throwaway line; it’s a manifesto. The accompanying references to Merteuil, described as “la série la plus sulfureuse de la rentrée,” position her as an actress stepping into roles that mirror her own reinvention. The French phrasing—“sulfureuse,” “oser”—carries a weight of provocation, suggesting danger, allure, and a refusal to conform.

Culturally, the styling nods to a lineage of French editorial minimalism: think Helmut Newton’s stark contrasts or Carine Roitfeld’s stripped-back seduction. The black dress, the bare shoulders, the upward gaze—these are not just fashion choices, they’re cultural signals. They place Kruger in dialogue with a tradition of women photographed not as muses, but as forces.

Hair is swept back or left in soft waves, makeup neutral yet sculpted—every detail designed to amplify the tension between restraint and sensuality. Jewelry, when present, is minimal or symbolic, like the Vivier bracelet glimpsed in one spread, serving as punctuation rather than ornament.

The cohesion is striking: text and image echo each other, both insisting on autonomy, both daring the viewer to look closer. It’s not just a fashion spread—it’s a meditation on control, reinvention, and the art of being seen.

Would you call it mystery, or mastery? Either way, Kruger has already claimed both.

Share what you think